Hatra - An Arab Kingdom in Roman Times

Professor Wathiq Ismail al-Salihi

Wednesday 16 November 2016

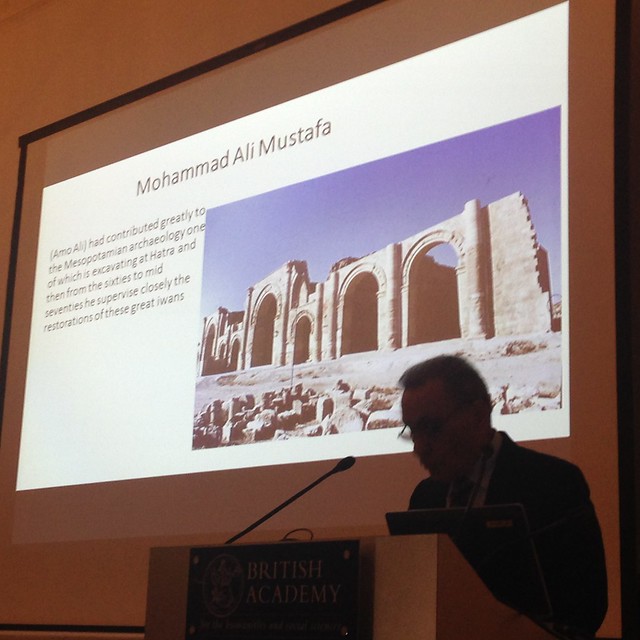

For a full house at the British Academy, Professor Wathiq Ismail al-Salihi gave a lecture in memory of Mohammed Ali Mustafa, the "sheikh of excavators in Iraq", sponsored by Dr Sabah and Mrs Sumaya Zangana.

Professor Al-Salihi spoke for over an hour about the ancient city of Hatra, where he had previously directed the excavations of various monuments and buildings. Situated a good 100 km to the southwest of Mosul, Hatra is said to have been located along a relatively minor trade route and the existence of its tribal society depended on access to the available water resources through wells.

Throughout his talk Professor al-Salihi emphasised what he called the formidable fortifications of the city, whose defence system famously withstood the attacks of two Roman emperors, Trajan and Septimius Severus, before finally falling (around AD 240) to the Sasanians, who had established themselves as the major power in the region after defeating the Parthians. The circular walls were 3 m wide with mudbrick on foundations of hewn stone, and curtain walls of hewn limestone slabs were added. A large moat, 4-5 m deep and 8 m wide, surrounded Hatra. A bridge over the moat, supported by an arch, was leading to an entrance into the city. Close to the gate, the number of buttresses increased. According to later Arab authors, Hatra’s walls were protected by talismans. A gorgon head decorated the fortifications. A ballista (stone thrower) that was used in the defence against Severus was found near the North Gate.

In the gates, with their lateral opening, were niches containing statues of an apotropaic deity commonly identified as Heracles-Nergal. A relief of an eagle stood above legal texts concerning the death penalty as a punishment for theft: a thief from outside Hatra would be stoned to death, whereas a thief from within the city would die the enigmatic ‘death of the god’ (see also T. Kaizer, ‘Capital punishment at Hatra: gods, magistrates and laws in the Roman-Parthian period’, Iraq 68 (2006), p.139-153).

Many of Hatra’s monumental buildings were constructed during the long reign, in the first half of the second century AD, of the local lord Nasru. He left two images of himself, inscribed with his name, on the voussoirs of one of the iwans, the large vaulted structures that are so characteristic of Hatrene architecture and are dedicated to the members of the local triad (Maren - ‘Our Lord’; Marten - ‘Our Lady’; Bar-Maren - ‘the Son of Our Lord’) and to other deities such as Shahiru - the Morning Star. The later king Sanatruq, together with his son Abdsmya, was responsible for the magnificent temple of Allat. Musical scenes of what has been interpreted as Dionysiac ritual decorated the sanctuary on the inside. The two central reliefs depict the goddess herself. On the first, Allat is welcomed, riding on a camel, by a nymph holding a balance. On the second, the goddess is seated on the lever of this same balance, a symbol of her justice. King Sanatruq approaches the goddess, and a model of the temple is presented to her.

Fourteen shrines were excavated elsewhere in the city, including no.XII to Nebu and no.XIV to Nanai. Finally, Professor al-Salihi showed images of a mural painting found in the North Palace, which he interpreted as an image of Aphrodite at her bath, as inspired by the Sixth Homeric Hymn.

Dr Lucinda Dirven of the University of Amsterdam, editor of an important recent volume on Hatra (L. Dirven (ed.), Hatra. Politics, Culture and Religion between Parthia and Rome [Oriens et Occidens 21] (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2013)), gave the vote of thanks.

Ted Kaizer, Durham University (ted.kaizer@durham.ac.uk)

Photos by Eleanor Robson